Frequently Asked Questions - National Carbon Fee and Dividend

Would carbon pricing be effective in reducing climate pollution?

What do studies say about the impact of carbon pricing on the Hawai‘i economy and its residents?

Would carbon fee and dividend make it even more expensive for families to live in Hawai‘i?

What would be the impact of carbon fee and dividend on Hawai‘i’s tourism industry?

How do carbon pricing and a green fee compare in addressing the environmental impacts of tourists?

How would carbon pricing interact with other regulatory policies?

How would carbon fee and dividend interact with the recently passed Inflation Reduction Act (IRA)?

What are the pros and cons of carbon fee and dividend relative to other potential climate measures?

Should Hawai‘i and other states also adopt carbon pricing policies?

What happens to the local policy should national pricing be implemented?

1. What would a carbon fee and dividend policy do?

The policy known as “carbon fee and dividend” would impose a fee on fossil fuels based on their carbon content and return all of the revenues (minus a small amount needed to cover administrative costs) to U.S. citizens and their dependents in the form of cash payments. Each adult would receive an equal share (the same dividends) and each minor would receive a half share.

2. Would carbon pricing be effective in reducing climate pollution?

Yes. The policies have been found to be effective in real life and more than 40 countries have implemented carbon pricing. The policy has proved effective in Sweden and British Columbia.

Numerous economic analyses have shown carbon pricing to reduce emissions. The magnitude of emission reductions is directly related to the level of the carbon fee. That is, the higher the carbon fee, the greater the amount of emission reductions.

For example, a carbon fee and dividend bill previously introduced in the U.S. Congress (HR 763) would start the fee at $15 per metric ton of carbon dioxide equivalent and increase it by $10 each year until the emission target is met. This fee level would increase the cost of gasoline by about 90 cents per gallon in 2032. The carbon fee would accelerate the shift away from fossil fuels, reducing greenhouse gas emissions by an estimated 20 percent in 2032 (An Assessment of the Energy Innovation and Carbon Dividend Act).

3. Why should the United States take action on climate change when countries like China and India are much bigger emission sources?

Addressing climate change is a collective action problem in which everyone needs to reduce their carbon emissions locally and nationally to make a difference globally.

China, India, and the United States together emit half of the world’s greenhouse gasses, but of those three countries, the United States emits the most per person by far. Furthermore, both China and India are already enacting policies to limit their own emissions, despite having much smaller carbon footprints per capita. They’re probably doing so because having strong climate policies will ultimately bring them economic and health benefits, and the United States should take action for the same reasons: the benefits of reducing fossil fuel emissions will far outweigh the costs.

Another reason to implement a carbon fee and dividend policy is to protect the international competitiveness of U.S. businesses. The European Union is starting to phase in a carbon border adjustment, and Canada is expected to follow soon after. The EU’s import taxes will start in 2026, initially applying to seven carbon-intensive sectors, including cement and steel. This means that if the United States fails to implement carbon pricing domestically, exports from the United States of fossil fuel-based products to those countries will be subject to tariffs, putting U.S. industries at a competitive disadvantage.

If the United States implements a carbon fee and dividend policy with a carbon price similar to that of the EU and Canada, U.S. businesses will avoid those tariffs in the European Union and Canada. Furthermore, the domestic carbon border adjustment that we would establish in concert with a domestic carbon fee would level the playing field for U.S. industries in the entire global marketplace and encourage our other trading partners to put a price on carbon.

4. What do studies say about the impact of carbon pricing on the Hawai‘i economy and its residents?

A study by Oxford Economics shows that a carbon fee and dividend program would benefit households in the first eight deciles by income. That is, on average, eight of ten households—all but the top-earning twenty percent of households—would experience an increase in their disposable income under a carbon fee and dividend policy.

The U.S. Department of the Treasury conducted a similar analysis. Its study shows that, on average, a carbon fee and dividend would financially benefit households in the lower seven deciles.

Two recent studies specific to the State of Hawai‘i indicate that carbon cashback would be effective in reducing carbon emissions, and would financially benefit all but the wealthiest households. The University of Hawai‘i Economic Research Organization (UHERO) study entitled “Carbon Pricing Assessment for Hawai‘i: Economic and Greenhouse Gas Impacts” (April 2021) was commissioned by the Hawai‘i State Legislature in 2019 to better understand the implications of a carbon tax and dividend policy. A follow-up study was sponsored by the State of Hawai‘i Tax Review Commission (TRC) via the State Department of Taxation. These two studies examined the economic impact on Hawai‘i households and businesses of a carbon cashback program with a carbon tax set at the Obama-era social cost of carbon ($50/MT in 2025 rising to $70/MT in 2045, in 2012 dollars). Key takeaways include:

If carbon tax revenues are given back to households in equal shares, a carbon tax is progressive—meaning this revenue recycling scheme benefits lower-income households more than proportionately. This progressivity occurs because higher-income households tend to consume more fossil fuels and more goods and services overall and are thus contributing directly and indirectly more of the carbon tax revenues.

A carbon tax set at … about $50 per metric ton (in 2012 dollars) of CO2 has small impacts on the overall economy. Returning revenues back to households in equal shares makes households economically better-off.

This policy would lead to a 10% reduction in cumulative CO2 emissions from 2025 to 2045

Based on the results of these studies, the Tax Review Commission’s 2021 Report to the Legislature recommended that Hawai‘i:

Impose a carbon tax to incentivize moving away from carbon-based fuels and adopting clean energy. We recommend that the majority of the proceeds be rebated as a cashback to the residents of Hawai‘i, with a disproportionate distribution to low-income households.

5. Would carbon fee and dividend make it even more expensive for families to live in Hawai‘i?

For most families, no. A 2020 study (Ummel) of the impacts of carbon fee and dividend on U.S. households estimates that 68 percent of households in Hawai‘i would actually come out ahead, as the dividend payments they receive would be greater than the increased prices they pay for fossil fuel products. In other words, living in Hawai‘i would become less expensive for most families, and this would be particularly true for lower-income households, which tend to consume fewer fossil fuel products than wealthier households. For example, (Ummel) estimates that 92 and 83 percent of families in Hawai‘i’s lowest and second-lowest income quintiles, respectively, would come out ahead.

6. Would people with long commutes be worse off?

People with longer commutes tend to consume more fossil fuel, so they would pay more in carbon fees, but the dividends would offset most or all those increased costs. For example, the 2020 study by Ummel finds that among rural households in Hawai‘i, which tend to drive longer distances than urbanites, 61 percent would come out ahead under carbon fee and dividend, and only 17 percent would see a drop in income of more than 0.2 percent

7. How would carbon fee and dividend affect electricity bills?

As utilities transition to using more and more renewables to generate electricity, the carbon price would have a smaller and smaller effect on electricity prices.

Also, the continuing decline in the price of renewables makes them more and more competitive with petroleum-generated energy.

The carbon price would enhance this competitiveness. The utilities would be essentially rewarded for producing more power from renewables. For example, electricity prices on Kauai, which has significantly more renewable energy generation than Oahu, are lower than Oahu’s petroleum-dominated electricity prices, and they would continue to be so until Oahu’s share of renewable generation approached that of Kauai’s.

In addition, the carbon price would incentivize more efficient operation of the existing fossil fuel-fired generating units.

8. What would be the impact of carbon fee and dividend on Hawai‘i’s tourism industry?

Hawai‘i tourism industry is relatively insensitive to changes in prices. The UHERO study finds that if Hawai‘i were the only state to implement the carbon cashback policy with a tax on jet fuel, only a very modest reduction in visitor spending (about 0.3%) would result. Part of the reason for the reduction is that some visitors from the Mainland would choose to vacation somewhere besides Hawai‘i because of the increase in costs. But if the entire country were subject to the same carbon prices, then Hawai‘i would experience a much smaller disadvantage (Hawai‘i would still likely experience some disadvantage because travel distances to and from the Mainland are generally farther than travel distances within the Mainland). That is, a national policy would likely have even less of an impact because the cost of a Hawai‘i vacation would increase less relative to a Mainland vacation under a national carbon pricing policy compared to under a Hawai‘i-only carbon pricing policy.

Existing economic studies and data suggest that a $50 per MT CO2 tax would increase costs on a typical Hawai‘i visitor by about $1.40 per day, or $12 per visit.

9. How do carbon pricing and a green fee compare in addressing the environmental impacts of tourists?

Carbon cashback would address direct and indirect carbon emissions that are caused by tourists. In some activities such as car rentals, the carbon tax would incentivize tourists to use less gasoline. Carbon cashback is designed to address carbon emissions.

A green fee would charge all tourists the same fee regardless of their carbon footprint. A green fee would be designed to address impacts on environmental resources (e.g., beaches and forests).

These two proposed policies could work together to help Hawai‘i’s residents, encourage sustainable tourism, and preserve Hawai‘i’s unique beauty and culture for future generations.

10. How would U.S. citizens receive their rebates?

The Federal government can use existing IRS and Treasury Department procedures to distribute the rebate (dividend). Doing so would avoid creating any new bureaucracy and minimize the risk of abuse and corruption.

11. Would carbon pricing promote social justice or diminish it?

Carbon fee and dividend is designed to promote social and economic justice. Carbon pricing mechanisms where revenues are retained by the government to implement climate programs, such as zero-emission vehicle rebates, do not promote social justice, since low-income residents are financially constrained, resulting in most zero-emission vehicle rebates going to higher-income residents. With zero-emission vehicle rebates, the government provides a source of relief from higher gasoline prices for higher income households and provides no relief to lower-income households. However, a carbon pricing policy with the tax revenue returned to residents in equal shares in the form of a climate rebate would provide lower income households financial relief from the higher energy prices. This policy is therefore progressive—that is, low-income households, on average, would financially benefit more than high-income households.

The Energy Innovation and Carbon Dividend Act (EICDA), which would establish a carbon fee and dividend policy, would improve health, save 90,000 lives each year due to cleaner air. and create a stable climate for everyone to enjoy. Because low-income communities suffer the worst from pollution, they would see the most benefit from this policy.

Additionally, most low-income people would come out ahead financially under this policy, thanks to the dividend, which puts money directly into the pockets of low- and middle-income people.

The UHERO study found that a carbon fee and dividend program where at least 50 percent of revenues are returned to residents would be progressive—meaning this revenue recycling scheme benefits lower-income households more than proportionately. This is because lower-income households, which tend to purchase fewer goods and services than higher-income households, would pay less carbon tax than higher-income households on average, yet receive the same climate rebate. The UHERO study and the UHERO study Appendix A find that by 2026 the lowest quintile households, on average, would come out $900 per year ahead while middle-income households, on average, would experience a financial gain of $500 per year.

12. How would carbon pricing interact with other regulatory policies?

Carbon pricing would strengthen and therefore complement most other regulatory policies that are designed to reduce carbon emissions. For example, energy efficient technologies would penetrate the market faster in the presence of both a carbon fee and efficiency standard because the carbon fee would lower the price of the more efficient technology relative to the less efficient one. In the case of Hawai‘i’s Renewable Portfolio Standard (RPS), a carbon fee would further incentivize the utilities to reduce their fossil-fired generation by improving the efficiency of existing fossil-fired units and bringing more renewables onto their systems.

13. How would carbon fee and dividend interact with the recently passed Inflation Reduction Act (IRA)?

It would increase the positive impacts of the IRA. The IRA is a big step forward in combating climate change. The IRA provides, through subsidies, financial incentives to consumers to purchase less carbon intensive technologies. However, Hawai‘i cannot rely on the IRA alone to achieve its 2045 net negative emissions goal. Enacting carbon fee and dividend would raise the price of technologies that use fossil fuels or that are more carbon intensive. Thus, the IRA lowers the price of cleaner technologies while a carbon tax would raise the price of dirtier technologies. The policies would work together to make cleaner technologies more cost-effective compared to dirtier technologies. Therefore, carbon fee and dividend would complement the IRA and increase its effectiveness. For example, the IRA provides incentives for people to purchase zero-emission vehicles (ZEVs). Carbon fee and dividend would create an additional incentive because ZEVs are less carbon-intensive per mile traveled than gasoline powered vehicles. Many of the benefits of the IRA will not be seen for many years because they accrue to future purchases rather than to changes in the operations of current technology (e.g., vehicles), whereas carbon fee and dividend would have more of an immediate effect because it addresses the operation of current technologies, thus encouraging people to conserve energy and operate their technologies more efficiently.

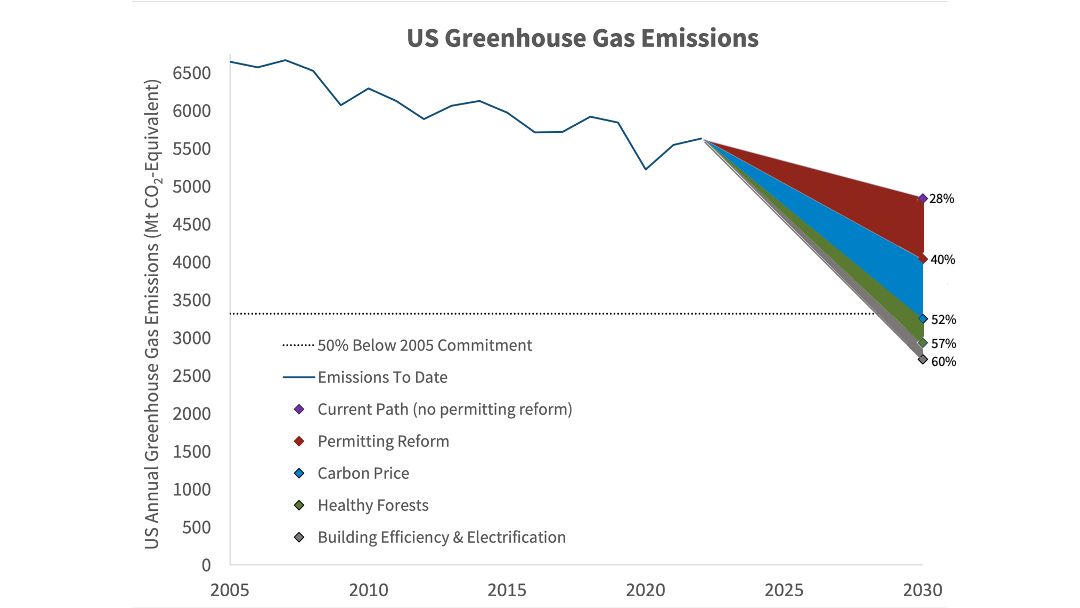

The figure below shows how a carbon fee and dividend policy like the Energy Innovation and Carbon Dividend Act (EICDA) would complement the recently passed Inflation Reduction Act (IRA). If only the IRA remains in place, then 2030 U.S. emissions are forecasted to be 28 percent less than 2005 emission levels, and if permitting reform is made, the reduction would be 40 percent (red area). If the United States were to implement the EICDA on top of those policies, 2030 emissions are forecasted to be 52 percent less than 2030 levels (blue area) and thus the country would meet its National Determined Commitments (NDCs) of the Paris Accord. Therefore, national carbon pricing would complement the IRA and also help the United States meet its internationally agreed upon national targets.

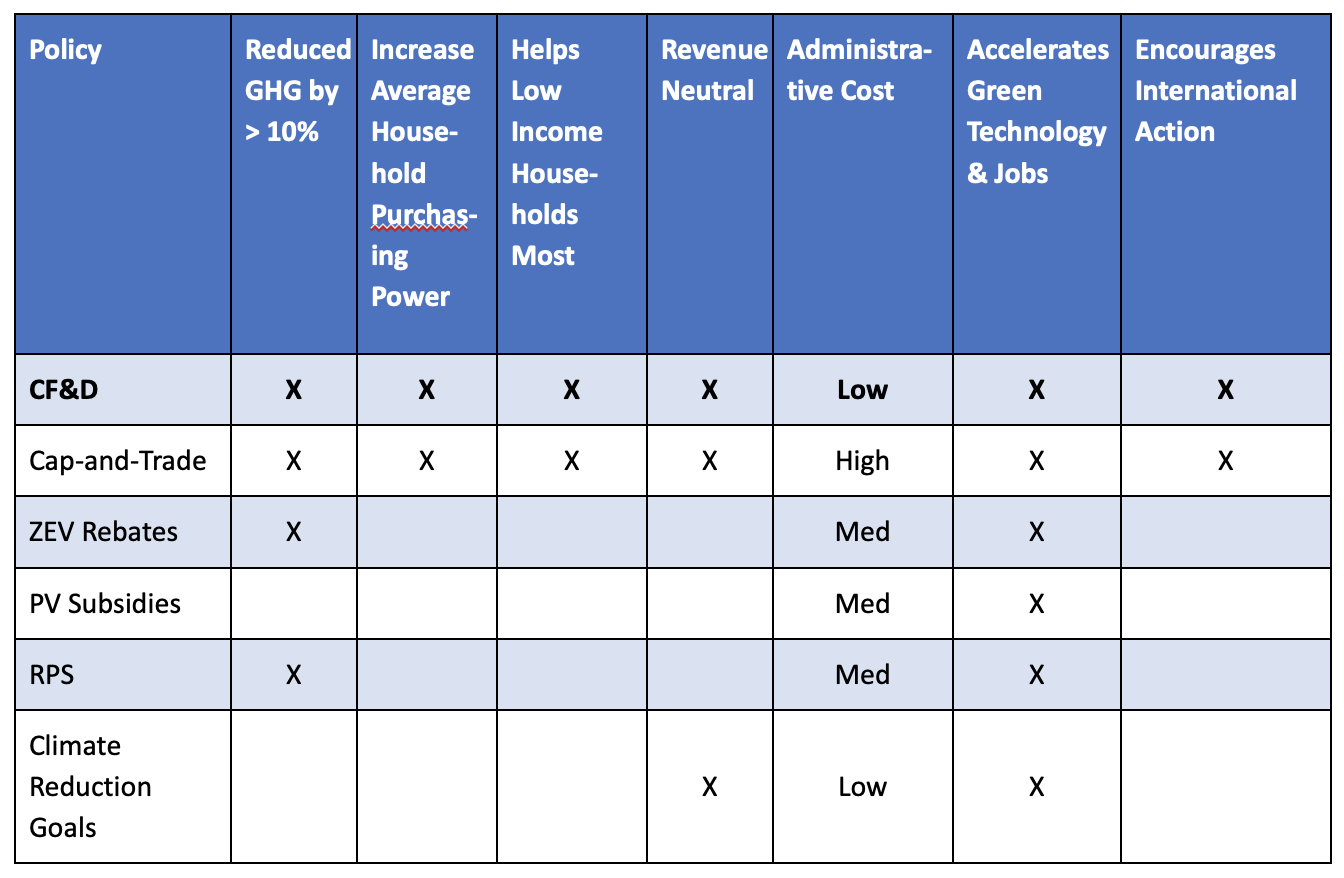

14. What are the pros and cons of carbon fee and dividend relative to other potential climate measures?

The table below summarizes the benefits of carbon fee and dividend to Hawai‘i and its residents relative to other potential climate programs.

Notes:

1) The Carbon Fee and Dividend and Cap-and-Trade programs are assumed to return all revenues less administrative costs back to households. The emission reductions achieved from either policy depend on the carbon tax or cap, respectively, but they can easily be designed to achieve well over 10% emissions reductions

2) TRC = Tax Review Commission

3) RPS = Renewable Portfolio Standard

4) ZEV = Zero emitting vehicle from the tailpipe

5) Climate Reduction Goals are assumed to be non-binding; hence no enforceable reductions

15. Who supports carbon pricing?

There is broad support for pricing pollution as part of solving climate change, from Bernie Sanders to Dr. James Hansen, former Federal Reserve chairpeople, and Republican elder statesmen. Across the political spectrum, people see carbon pricing as an effective tool for reducing emissions. Two-thirds of Americans favor taxing corporations based on their carbon emissions, according to a recent Pew Research Center Survey. Below are several references from various entities and people that see carbon pricing as a necessary policy.

Placing a price on carbon pollution has been endorsed by thousands of economists, including 28 Nobel laureates, four former Chairs of the Federal Reserve, and fifteen former Chairs of the Council of Economic Advisors, who have collectively said that “a carbon tax offers the most cost-effective lever to reduce carbon emissions at the scale and speed that is necessary.”

Also supportive are the U.S. Chamber of Commerce and Business Roundtable, religious groups, Pope Francis, and many prominent individuals and businesses.

The American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy states that carbon pricing “would help equalize the market environment between electric end uses and fossil fuels and could be the single most impactful policy to drive building electrification forward on the federal and state levels.” (C. Cohn and N.W. Esram, 2022, Building Electrification: Programs and Best Practices.

The World Bank asserts that carbon pricing is the most effective way to reduce climate pollution.

The Group of 20 (G20), which includes the United States, the European Union, China, and India, representing ninety percent of the world’s economy, encourages the appropriate use of carbon pricing when used among a wide set of tools to control climate change.

A recent report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change reinforces the need for action and reminds us about what is at stake. When it comes to action, the IPCC report says, “Pricing of greenhouse gases, including carbon, is a crucial tool in any cost-effective climate change mitigation strategy, as it provides a mechanism for linking climate action to economic development.” For more on what the latest IPCC says about carbon pricing, please click this link.

The International Monetary Fund calculates that the failure to tax fossil fuels to properly reflect and discourage their social and environmental damage represents a global subsidy of $420 billion every year to the oil and gas industry.

The premier carbon fee and dividend bill introduced in the last Congress, the Energy Innovation and Carbon Dividend Act, had more than 90 Democratic co-sponsors, including at least 42 members of the Progressive Caucus, 14 members of the Congressional Black Caucus, 13 members of the Congressional Hispanic Caucus, and 29 members of the Congressional Asian American Caucus. Those members realized that the causes of economic and environmental justice are best served by a powerfully effective climate policy (carbon pricing) combined with a progressive allocation of revenue (carbon dividend or cashback).

Senator Bernie Sanders wasn’t speaking for oil companies when he declared, “A carbon tax must be a central part of our strategy for dramatically reducing carbon pollution . . . a carbon tax is the most straight-forward and efficient strategy for quickly reducing greenhouse gas emissions.” Nor were two Jacobin magazine writers when they published an essay, “Why Socialists Should Back a Carbon Tax.” Nor was the CEO of the sustainability advocacy group CERES when she backed carbon pricing. Nor was the California Environmental Justice Advisory Committee when it supported a carbon fee.

The renowned climate scientist James Hansen says it would be “the most effective and direct underlying force for a global climate solution.” The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine issued a major report in 2021 on Accelerating Decarbonization of the U.S. Energy System which declared, “The advantages of an economy-wide price on carbon are that it would unlock innovation in every corner of the energy economy, send appropriate signals to myriad public and private decision-makers, and encourage a cost-effective route to net zero.”

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, representing the best experts from around the globe, reported last year, “Pricing of greenhouse gases, including carbon, is a crucial tool in any cost-effective climate change mitigation strategy, as it provides a mechanism for linking climate action to economic development.”

The Lancet Commission on Health and Climate Change, representing some of the world’s leading public health authorities, declared in 2015: “The single most powerful strategic instrument to inoculate human health against the risks of climate change would be for governments to introduce strong and sustained carbon pricing, in ways pledged to strengthen over time until the problem is brought under control. Like tobacco taxation, it would send powerful signals throughout the system, to producers and users, that the time has come to wean our economies off fossil fuels, starting with the most carbon intensive and damaging like coal.”

Paul Hawken, author of Drawdown, expressed his support of pricing at the October 2022 UH Better Tomorrow series webinar. “Carbon pricing is definitely the most significant single policy that there could be.”

Anu Hittle, former Hawai‘i State Climate Change Mitigation and Adaptation Coordinator, wrote in a 2020 post, “If you agree that life, property and nature are worth preserving (and are hurt by CO2 because it produces climate change), then a carbon tax can be a good thing because it could make us choose items that are “carbon-free” and so, a lifestyle that encourages the preservation of the things we value—healthy people, markets and ecosystems.”

Leah Laramee, Hawai‘i Climate Change Mitigation and Adaptation Commission Coordinator, offered the following in her supportive testimony for HB1146 (Carbon Cashback bill): “This measure is the most effective tool in a suite of policy tools that need to be undertaken, and is one that would address much needed equity and regressivity issues that already exist in Hawai‘i.”

16. Should Hawai‘i and other states also adopt carbon pricing policies?

Ultimately, we need to have national carbon pricing, particularly because it could include a border carbon adjustment that maintains the competitiveness of U.S. businesses. But pending national action, we should implement local carbon pricing as soon as possible for several reasons:

State-level action can inspire other states, and ultimately the national government, to follow. Hawai‘i can lead the way to show that carbon pricing can be progressive, easy to implement, and reduce emissions. This opportunity to lead is not new to Hawai‘i. We’ve been leaders in climate policy that have inspired national action. Our 100% Renewable Portfolio Standard mandate is an example.

National carbon pricing will take time to implement. By implementing a price on carbon locally, we are able to promptly tackle emission reduction at the state level.

A local carbon price can also catalyze other policy, process, and technology innovations related to carbon reduction. It will encourage people and companies to identify low-carbon solutions that would otherwise not be implemented.

17. What happens to the local policy should national pricing be implemented?

The local carbon pricing policy should include provisions that allow for it to be superseded by national policy as long as the national policy employs the same or greater level of carbon pricing.